A few weeks ago, I had a minor breakdown at the dinner table. The dinner I had spent 30-40 minutes making was NOT good. In fact, it was inedible. When I apologized for the disaster, my sweet husband assured me it wasn’t my fault that the recipe wasn’t as good as it sounded, while simultaneously ordering delivery. But for me, it was about much more than one bad dinner. In my mind, the failure of this dinner was a waste of time, energy, and money, and now we were wasting more money to order take-out.

I loathe every aspect of making dinner. Meal planning stresses me out because I am constantly trying to find a balance between choosing meals that are good for my family, choosing meals they will actually eat, and choosing meals that aren’t difficult or time-consuming to cook. Cooking is the last thing I ever want to do after a long day of work. It does not relax me as it does for so many others, I’m terrible with timing things out, and I have no idea how to season anything without a recipe. At least one of my kids is guaranteed to refuse to eat the meal and will probably tell me it’s gross or throw a fit over being asked to try it. And then, of course, I have to clean up the kitchen. I spend an hour or more every day working to feed my family for ten minutes of sustenance, and it is NEVER EVER good enough to be worth the effort.

When I share my frustrations with my friends on social media, a few friends will chime in with “me too!” and a few more will offer suggestions for making meal planning easier, but I’m not sure anyone quite gets the level of frustration meal planning and cooking brings me to. I don’t want it to be easier. I simply don’t want to be responsible for it at all, but since my husband works late and we live on a budget, it is not a chore I can outsource to someone else.

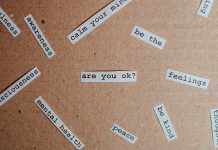

I have lived with this frustration and accepted that cooking is just one of those aspects of “adulting” that I have to do because my family needs to eat, no matter how much I dislike it. But a recent trip to the pediatrician caused a light bulb moment, and I suddenly realized that food, and in particular, being responsible for the food my family consumes, is actually a trigger for my anxiety.

To be clear, I have never struggled with an eating disorder. My parents raised me with an “everything in moderation” mindset. I have always been a fruits and veggies kind of girl, and when I visit my parents, the comfort foods I request include stuffed peppers, turnips, Brussel sprouts, and my dad’s homemade applesauce. Outside of the fact that I am a chocoholic, “healthy” eating has never been an issue for me, but I’ve also never been one to get particularly thrilled about food either. I’m not one to get excited about trying a new restaurant, I’m not impressed by food trends, and while I can enjoy fried chicken or a traditional eggs and bacon breakfast, regularly eating heavy foods (so common in the South) leaves me feeling sluggish and cranky. If I lived on my own, I’d just pick up a prepared meal from Whole Foods every day, but this isn’t a realistic solution for my family.

So how exactly did the trip to the pediatrician lead me to this discovery? Well, both of my kids are considered “overweight” on the BMI chart (my irritation with that is another post entirely). As the pediatrician and I discussed their weight, I felt the implication was that I was not doing enough to help my kids stay healthy. Certainly, the doctor was just making suggestions and comments, part of her job, but I felt that a lot of these suggestions were things I was already doing for my kids or things I wasn’t going to force them to do for the sake of proving I was doing everything I could to help them develop healthy habits. For example, she discouraged me from letting my kids drink their calories by consuming a lot of juices and sodas, but my kids mostly drink water, and they don’t even like soda. She suggested that they don’t need to eat fast food regularly, but we don’t. She encouraged me to sign them up for sports, but we’ve tried several. My kids simply don’t enjoy them, I wasn’t an athletic child either, and it doesn’t seem worth adding to the weeknight stress just to force them to be involved in activities they don’t enjoy. I can almost guarantee that stress would result in more fast food consumption when the alternative is to continue allowing them to play outside with their friends while I cook at home. She also suggested I limit my kid’s intake of sweets, while simultaneously acknowledging that part of my oldest’s struggle with ADHD is impulse control. We teach her about healthy choices and limit the junk she consumes in our house, but I don’t have control over the food she gets at school parties and friends’ houses, and I know she’s not always making the best choices, despite what we’ve taught her.

In other words, the message I walked away from that day was that, despite my best efforts, I would always be judged for my family’s weight and eating habits. This puts so much pressure on me when it comes to meal planning and cooking. Add in the voices of 90’s diet-culture-past that influenced my teenage years and my husband’s opinions on sugars and carbs, and making choices about what constitutes “healthy” eating for my family seems like an impossible task. I will never “win” at feeding my family. If the meal isn’t good, I lose money. If my kid’ like it or if we order out because I’m too tired to cook, I’m probably setting them up for future battles with obesity and diabetes. If I like the food, everyone else will complain that they don’t, and I’ll wonder why I bother trying.

I know some people will say I’m overthinking all of this and putting too much pressure on myself, but the pediatrician suggests that’s I need to do more; the schools stress the importance of sending “healthy” options for snack time; my kid gets called “fat” by her classmates; and society tells me I need to teach her about healthy choices and body positivity. No matter what direction I turn, I am reminded that their health is my responsibility and that there are dire consequences if I fail. Maybe if I actually loved food or enjoyed cooking it wouldn’t be so overwhelming, but more often than not, it feels like the literal weight of my family’s health depend on my ability to perform a task for which I have neither talent nor interest, and too frequently, my best efforts get scraped into the trash, either immediately or as week’s old leftovers that no one reconsidered.